This was many years ago when my wife and I moved to Los Angeles from New York and installed ourselves in a 7 room apt on Berendo street for $175 a month. That is correct. My wife got a job and I stayed home to write or try to. Each day I would sit down at the typer to bang and I would try this sentence and that sentence and the other sentence but it was no dice. There was nothing. Writing must have energy. Here there was the energy of a piece of pocket lint. It was a form of literary constipation.

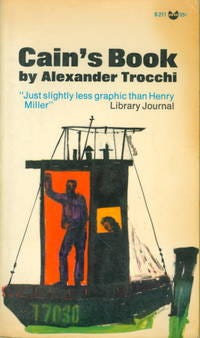

But if you cant write you can at least read other writers who are. I was at Book Soup on Sunset waiting for my wife to finish work. I picked up a book—Cain’s Book. The writer was Alexander Trocchi. I’d heard of this book—from Hank in San Francisco, fellow writer or writer wannabe. He said: I think you would like it. Its brilliant. There was a blurb on the cover: The genuine article on the dope addicts life.

The publisher was Grove Press. This was the sixties and in the sixties there was a particular kind of writer—the Grove Press writer. Publishers have something called a stable, like a horse stable but instead of horses they have writers. In Groves stable were Henry Miller, Beckett, Jean Genet, Celine, etc, the renegade outcast types—perverse, nihilistic, scatological. I read a few bits and pieces. There was a preface, a quote from Cocteau:

Tout ce qu’on fait dans la vie, meme l’amour, on le fait dans le train express qui roule vers la mort. Fumer l’opium, est quitter le train en marche, est s’occuper d’autrechose que de la vie, de la mort.

I translate though the French says it better: Everything we do in life, even to make love, we do on a train that is rolling towards death. To smoke opium is to leave the train en route; to concern ourselves with other things than life, than death.

Also:

Ettie was a thin negress who shot up ten five dollar bags a day. She pushed everything, clothes, meat and other valuables she boosted, her own thin chops. Man its a hassle what you do, I said to her, peddling around town all day with the heat breathing down your neck. He kin breathe right up my vagina dear, jist so long as he dont bust me, Ettie said.

Also:

Claire was my sister-in-law. She didnt like me. Nor was I fond of her. My brother was devoted to her. He did everything for her and his reward was to receive the impression he did not exist. She would have betrayed him for a dry martini.

I liked that line about the martini. It was perfect.

I bought the book and knocked it off that night. It was short but not too short, 50,000 words, the perfect length for a book, as Poe has said, to finish off in one sitting. Hank was right: an amazing writer.

The book is autobiographical, written in the first person by Joe, writer/junkie type living on a barge tied up in the Jersey docks across from New York. There is no plot. The action such as it is revolves entirely around Joe and his fellow junkies shooting dope or, when they are not doing that, running around in a frazzled state trying to score for dope. Here and there are flashbacks to his childhood and some good sex scenes.

Thats the book. But there was something about it—a rhythm. It wasnt a linear rhythm. It was a non-linear rhythm. I was reminded of Beckett and the way the element of time got bounced around—now here, now there, now somewhere else. The voice was strong—elegant, comic, salacious.

All great art and today all great artlessness must appear extreme to the mass of men as we know them today. It springs from the anguish of great souls. From the souls of men not formed but de-formed in factories whose inspiration is pelf. The critics who call upon the lost and beat generations to come home, who use the dead to club the living, write prettily about anguish because to them it is an historical phenomenon and not a pain in the arse. But it is pain in the arse and we wonder at the arrogance of governments that they should frown on the violence of my imagination which is a sensitive responsive instrument and set their damn police on me who has not stirred from this room for 15 years except to cop shit.

I went to the library to further investigate this Trocchi character but the pickings were slim. He had written Cains Book and another called Young Adam, long out of print. Also a handful of porno novels while living in Paris for Maurice Girodias & Olympia Press—the European version of Grove. There was reference to a writers conference in Scotland organized to discuss the current state of Scottish letters and Trocchi was invited to participate and his turn arrived to speak and he said: the greatest Scottish writer is me.

One of the other participants, a poet, Hugh McDiarrmid, referred to him as “cosmopolitan scum”.

And that was it. Some years later, many years later, a movie was made from Young Adam and a modest revival of interest in Trocchi was the result. Cain’s Book was reissued in a new edition and a few copies of the porno novels, White Thighs, Helen and Desire, Thongs, could be had at an inflated price on eBay. The movie, not a bad film, in fact a good film, flopped. I was curious to know, though I never did know, how much the writer of the script got paid. My guess is much more than Trocchi ever made for anything—or everything—he ever wrote.

Meanwhile there on the internet I came across a piece written for an English mag—The Guardian—to coincide with the release of the film that filled in some of the holes bio-wise.

Trocchi was Scottish, or Scottish/Italian, born in Glasgow in 1925. He attended the university, married young and had two children. He wanted to write and in view of this, in his opinion, Scotland was a loser. The action was in Paris. Once in Paris two things happened. He met Beckett and acquired a girlfriend, an American with money. The money was important because he had conceived a plan: to publish a magazine. Writers write to publish and if the publishers decline you can always publish yourself. Why not? Trocchi had a gift. He had two gifts. He had the writing gift and he had the hustling gift. He had charisma, a terrific magnetism that drew people into his orbit and this he combined with gift #3, the ability to manipulate these people to satisfy his needs which were: sex, drugs, money.

Any journalistic enterprise needs an angle and he had one—the existential angle. It was the fifties in Paris and there was a mood—the existential mood. Existentialism is a slippery concept that can be interpreted in this way, that way or the other way but however you interpret it the one word that will never apply is: optimism. The war had finished that one off in spades.

So that was the angle and in view of this the writers he chose to zero in on to get the mag rolling were the Olympia/Grove Press type: Beckett, Genet, Robbe-Grillet. He had a name for the mag: Merlin. The life span of the average small press literary magazine is measured not in years but issues. They are issued monthly or quarterly or annually and if you manage to give birth to a half dozen numbers of the publication before your money or your enthusiasm expires youre doing ok. Merlin held on for 3 years and during that time established a bit of reputation—for the quality of the writing and the brilliant—and brilliantly erratic—behavior of the editor. By this time he was on the junk, his wife and children had returned to England and less of his time was spent writing and more hanging out in cafes playing pinball. He was a drug addict and a pinball addict. He writes of the game in Cains Book:

In the pinball machine an absolute and peculiar order reigns. No skepticism is possible for the man who by a series of sharp and slight dunts tries to control the machine. It became for me a ritual act. Man is serious at play. Apart from jazz the pinball machine seemed to me to be Americas greatest contribution to culture; it rang with contemporaneity. The distinction between the French and American attitude towards the tilt (teelt); in America, and England, I have been upbraided for trying to beat the machine by skillful tilting. In Paris that is the whole point.

That was the first phase: the Paris phase. The second phase occurred in New York. It seems a questionable move for a junkie to relocate from Europe, that adopts a much more permissive attitude towards dope, to a country such as this, the US, with the most penal and pitiless laws concerning this evil habit.

But here he was living on a barge, scoring for dope and trying to write a novel—Cain’s Book. He had a new girlfriend—a hooker. She wasnt a hooker when they met. She became a hooker after Trocchi turned her on to junk and now there was a double habit to support and this was the solution—for her to become a hooker—they arrived at. He had a contract to write a book for Grove Press wangled by an editor, Dick Seaver, a Trocchi groupie from the Paris days. Trocchi as I say was a master con artist who by this time had burned half a dozen publishers for advances but not Seaver over at Grove, who knew his man and kept him on a short leash. There was no advance. He got paid by the chapter. This was the book that became Cain’s Book.

After that not much. He got busted for drugs, not only using but dealing. Seaver got him sprung on bail that he promptly forfeited by fleeing the country, first to Canada and then back to Europe, this time to England.

Yeah the joint. That wasnt for me. I remember Geo getting busted. The girl he was living with finked on him and one day they came pushing him back into his room, treating him like cattle. Ok Falk, we’ve come for you. Wheres your stash knucklehead? This time they put him in the Tombs. If anything had broken him it was kicking his habit in the Tombs. When he thought of it he thought of destiny and he felt himself without will. He was in a cell with a young Italian. Geo was in the bottom bunk. In the top bunk the Italian was sobbing. Why didn’t the bastard shut up? They wouldnt give him anything, not even a wet cotton. For a murderer yes but not for a junkie, a junkie couldnt even get an aspirin. Then he felt the wetness on the back of his hand. Jesus Christ! It was blood. The Italian was committing suicide. Call the man. The man took a long time to come and when he came he said: Why you dirty little junkie bastard! They dragged him out bleeding at both wrists.

Back in England the writing dried up. There was the occasional story, review, magazine piece but the sustained energy and discipline required to write a novel was gone never to reappear. Once a junkie always a junkie.

At some point, in London, he got into business selling books. He was a good businessman, oddly enough, and was able to make a living wheeling and dealing in the antiquarian book trade, working out of a stall in a fleamarket. He had a new girlfriend, a young girlfriend, the best kind, and it was in her arms following one last shot of heroin that he died in 1984, age 58.